Investigating an invasive species: The impact of Spongy Moths

Photos provided

In nature, nothing takes place in a vacuum.

That’s one of the most important lessons that Doug Robinson’s Ecology class learned in the Fall 2024 semester as they investigated the boom in the Hudson Valley’s Spongy Moth population that occurred this past summer.

Spongy Moths (Lymantria dispar) are an invasive species that were introduced to the United States in the 1860s in hopes of developing a silk industry, said Robinson, an associate professor of Biology and Study Abroad Academic Coordinator at the Mount. But not only did that experiment fail, but it failed spectacularly: Spongy Moths are now a major pest in North America. For example, in their caterpillar form, they can chew through leaves at an alarming rate and their waste can prevent absorption of nitrates – essential nutrients for plants – into the soil.

What’s worse, said Robinson, is that “native predators like birds don’t feed on them because they don’t recognize it as a food item.”

About every 10 or 15 years, there are breakouts of the Spongy Moth population. This summer saw such a breakout in the Hudson Valley, among other places. On a camping trip, Robinson noted Spongy Moth egg casings on virtually every tree he investigated. And that got him thinking.

“It would be really interesting to look at the egg case placement on the trees following the mass mating of the Spongy Moths that was taking place,” he said. “Why not take this idea into my Ecology class, where we discuss the relationship between a number of organisms and Lyme disease?”

But what does Lyme disease have to do with Spongy Moths? Remember: nothing in nature takes place in a vacuum.

Deer are often associated with Lyme disease because they carry ticks that transmit the illness, Robinson said. “But it’s an interplay between white tailed deer, white footed mice, and Spongy Moths and creates this interesting dynamic between food and prey, and the passage of Lyme disease from one organism to another – including potentially getting over to humans.”

Mice, explained Robinson, are “an excellent reservoir” for Lyme disease. First, ticks bite mice and become Lyme carriers before latching on to deer, infecting them with the disease as well. These ticks can potentially then attach themselves to a human.

Mice, as it turns out, love to eat the egg casings left by Spongy Moths. Thus, the more egg casings, the higher the potential for more mice. More mice means possibly more Lyme carriers and more infected ticks. And it all could come back to bite humans – literally.

“What looks like a single species problem…is actually a whole ecosystem problem,” said Robinson.

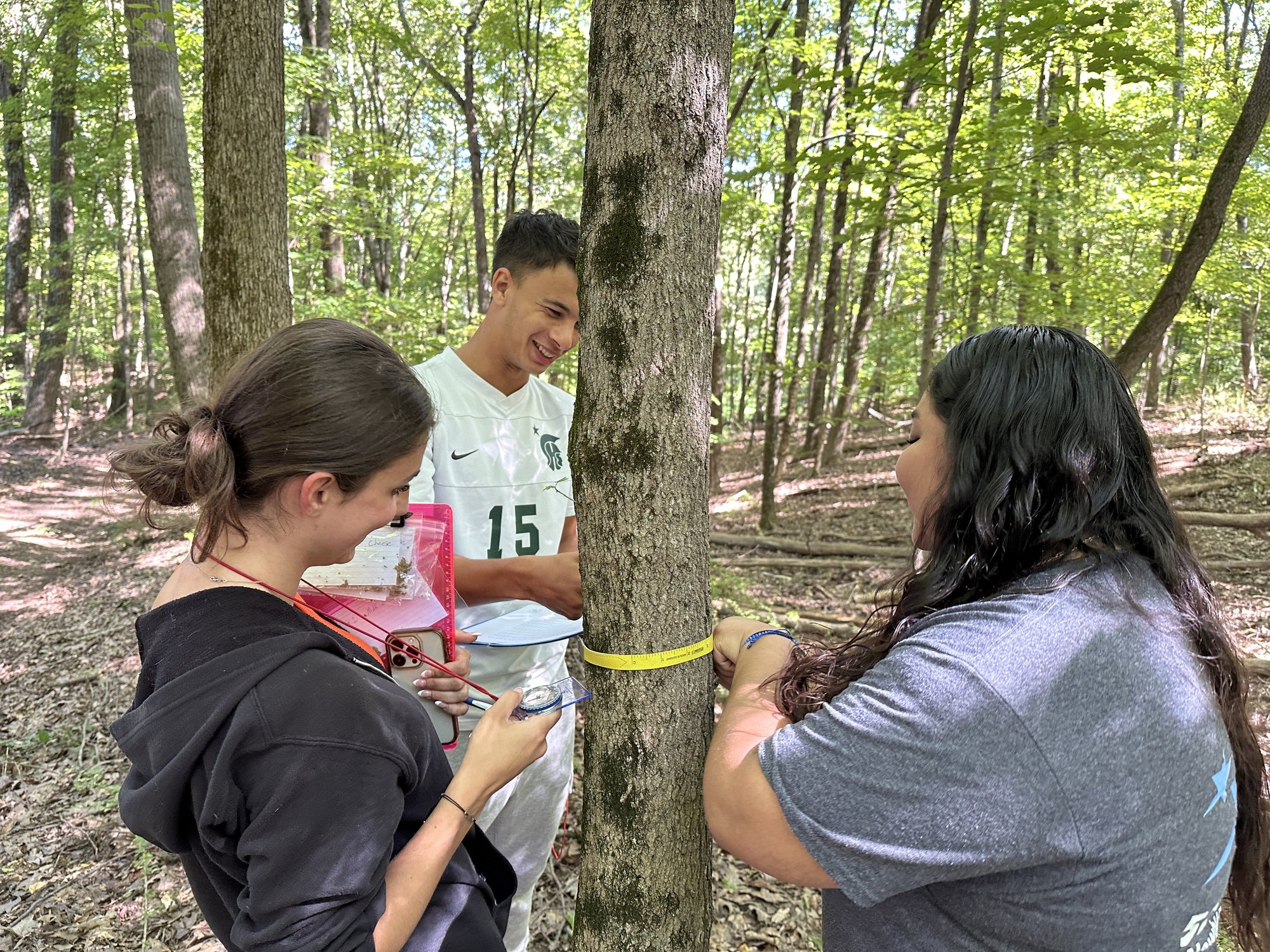

So in the Fall 2024 semester, Robinson’s Ecology class had the opportunity to “see Ecology at work,” he explained. The class found Spongy Moth egg casings on trees and counted the number of eggs in the egg masses that they collected. Robinson described the egg casings as approximately the size of a half dollar. There was an average of about 25 egg clusters on each tree, and each cluster could house anywhere between 48 to 520 eggs, Robinson’s class found.

The class collected 32 clusters, one per tree, and counted a total of about 9,400 eggs, each no bigger than a grain of sand. Keep in mind that this was just one small sample, meaning the number of Spongy Moths in the area this summer was staggering.

One of the most important lessons imparted to the students through the project is that humans are directly impacted by changes in the environment. It might be easy to forget that while sitting in a climate-controlled classroom, sleeping in a warm bed, or sipping on coffee at the local café, but we are indeed still part of the natural order.

“The environment around us does play an important role in human health,” said Robinson. “It’s not just something to look out the window and say ‘Oh, it’s pretty’ or to go out and take a hike…If we have these [pest] outbreaks occurring, they could potentially be correlated with human-related diseases, like Lyme.”

Another important lesson, he added, was simple: “Ecology is part of our wellbeing. A healthy environment means healthy people.”